Hug Machine

by Scott Campbell

Atheneum, 2014

I love this book. I love it up. Indeed, here is a place where one is glad one is blogging, and can set aside the more formal trappings of professional writing and just gush with abandon.

Ready? Here is a list of my impromptu enthusiasms:

1) The faces. Campbell does some good faces. His style is particularly loose and sketchy, but boy, howdy, he can capture emotion and attitude in a few watercolor gestures. From the resolute purpose of the hugger, expressed in his firm mouth and closed eyes, to the variety of surprise among those being hugged (catch the look on his dad’s face, and that turtle?! shut up!), the priceless range of emotion adds meaning and depth to what might have been one note mawkish.

2) The composition. Some spreads are open, and some are crowded. But whether it’s the ominous space between the hug machine and his intended porcupine, or the busy, serial hugging along the dotted line (a la Family Circus), the composition is never accidental and always effective.

3) The font. Everything is hand painted, with the same easy watercolors as the pictures, reinforcing the child-perspective and adding to the insouciance.

4) The arc. It’s not uncommon to happen upon a picture book whose words and images match its listeners. But I can’t remember the last time I encountered a book whose story arc was so well calibrated to its audience. The pagination, the pacing, the implicit pauses and inflections. Here is a book that will blossom when read aloud, over and over (and over).

5) The details. They got everything right here. The buff heavy stock feels delicious under your fingertips. The endpapers, with their empty and completed checklists, even the author flap of the dust jacket (with our hero hugging a fire hydrant while a curious dog looks on), all of it contributes to a cohesive, thorough, and endlessly appealing experience.

6) The edge. I’m not exactly allergic to sincerity, but I do like my earnest cut with a healthy dose of dry. This is an undeniably sweet outing, but between the bodacious humor and the appreciable astringency, it is anything but cloying.

7) The timing. Hug Machine did not come out in February (see above).

8) The gender expression. This is a book all about warmth, doused in pink and glowing with ardor, and the bearer of all of that fervent affection is a little boy. Boom.

I leave you with an instructional video on 90-second hugs by the author himself. I suggest you put in some practice, and then go out and get your hug on.

p.s. September 6-14, 2014 appears to be Hug a Book Week, so if you’re looking for a recipient, you might start at your local library.

ve War Horse: Based on a True Story

ve War Horse: Based on a True Story Stubby the War Dog: The True Story of World War I’s Bravest Dog

Stubby the War Dog: The True Story of World War I’s Bravest Dog Sparky!

Sparky! The Caldecott terms and criteria constitute a particular, prescriptive lens through which to look at picture book illustration. The Caldecott Medal is arguably the most prestigious prize a picture book can win, and as such the specific elements and attributes it recognizes have a particular role to play as we examine and evaluate books in the canon. To be sure, the Caldecott terms and criteria are not the only measure we can apply. Indeed, in our day to day work with children, other things–iconic characterization, accessibility, suitability for a group read aloud–can be much more significant. Still, measuring picture books with the Caldecott measuring stick allows us to delve deeply into the quality of the illustration, and gives us meaningful information about the application and legacy of the Medal itself.

The Caldecott terms and criteria constitute a particular, prescriptive lens through which to look at picture book illustration. The Caldecott Medal is arguably the most prestigious prize a picture book can win, and as such the specific elements and attributes it recognizes have a particular role to play as we examine and evaluate books in the canon. To be sure, the Caldecott terms and criteria are not the only measure we can apply. Indeed, in our day to day work with children, other things–iconic characterization, accessibility, suitability for a group read aloud–can be much more significant. Still, measuring picture books with the Caldecott measuring stick allows us to delve deeply into the quality of the illustration, and gives us meaningful information about the application and legacy of the Medal itself.

Grandma

Grandma The buzz leading up to the

The buzz leading up to the

For our winner we selected

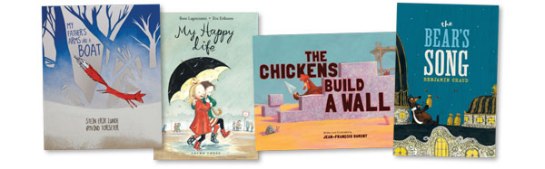

For our winner we selected Our honor book is My Father’s Arms Are a Boat by Stein Erik Lunde, illustrated by Øyvind Torseter (Enchanted Lion Books). A boy who recently lost his mother steps into the night with his father to process grief, look for comfort, and reconnect with the world that still holds possibility. Here we appreciated the untethered compositions, expressing the amorphous, rudderless nature of grief; the gradual relief that comes with the return of regular boundaries; and the expression of life’s fragility in the delicate three-dimensional paper-work dioramas.

Our honor book is My Father’s Arms Are a Boat by Stein Erik Lunde, illustrated by Øyvind Torseter (Enchanted Lion Books). A boy who recently lost his mother steps into the night with his father to process grief, look for comfort, and reconnect with the world that still holds possibility. Here we appreciated the untethered compositions, expressing the amorphous, rudderless nature of grief; the gradual relief that comes with the return of regular boundaries; and the expression of life’s fragility in the delicate three-dimensional paper-work dioramas. On Thursday, January 16, our regular Butler Center book discussion group, B3, resumes with a bang. This time out we’re conducting a Mock Caldenott Award. Yes, you read that right. CaldeNott. We’ll be using the official

On Thursday, January 16, our regular Butler Center book discussion group, B3, resumes with a bang. This time out we’re conducting a Mock Caldenott Award. Yes, you read that right. CaldeNott. We’ll be using the official  So, we have a short list of a butler’s dozen (that’s 13) extraordinary picture books vying for the Caldenott crown. You can find the titles

So, we have a short list of a butler’s dozen (that’s 13) extraordinary picture books vying for the Caldenott crown. You can find the titles  Hope to see you there!

Hope to see you there!