I lived with my sister, now a science education specialist, while she was completing her master’s degree. Her thesis considered students’ perceptions and assumptions of scientists: their work, appearance, and setting. We had a ball examining the teenaged participants’ drawings, through which an overwhelmingly popular archetype emerged: Einsteinian hair, glasses, bow ties, lab coats, Erlenmeyer flasks, boiling liquids, explosive gases. When asked “What does a scientist look like?”, students’ answer is almost unanimously male and inside a laboratory.

I am so pleased to see books for the young adult reader challenging the stereotype. Houghton Mifflin’s excellent Scientists in the Field series solidifies an altogether different image. Take The Tapir Scientist, by children’s nonfiction juggernauts Sy Montgomery and Nic Bishop. While the cover photograph shows the captivating and rarely seen face of a tapir – trunk-like snout, curious eye and nearly smiling mouth – the first title page’s photograph reveals the book’s namesake and star: a woman wearing dirty cargo pants, t-shirt and baseball cap wades through ankle-deep wetlands, holding an instrument in the air and peering towards the horizon. Her name is Patricia Medici, a Brazilian scientist whose work may more closely resemble extreme camping than the conventional image of “doing science.” For days, she and her team (which includes Sy and Nic) make trips around the vast Pantanal Wetlands of Brazil attempting to collar and track the elusive tapirs, whose behavior is largely a mystery. She has to beware pumas, venomous snakes, and the relentless bite of ticks, but the more troublesome battles are that with faulty equipment or inconsistent results. Although the subject of The Tapir Scientist and other books within this series is an animal, the text’s content is all process from the scientist’s point of view. Montgomery and Bishop record Patricia’s frustrations and triumphs as they happen and present their work as a narrative full of suspense, empathy and joy. Yes, the reader learns the traditional creature facts – anatomy, behavior, ecosystem – but all that report fodder is discovered only through the journey the reader makes with the scientist.

I am so pleased to see books for the young adult reader challenging the stereotype. Houghton Mifflin’s excellent Scientists in the Field series solidifies an altogether different image. Take The Tapir Scientist, by children’s nonfiction juggernauts Sy Montgomery and Nic Bishop. While the cover photograph shows the captivating and rarely seen face of a tapir – trunk-like snout, curious eye and nearly smiling mouth – the first title page’s photograph reveals the book’s namesake and star: a woman wearing dirty cargo pants, t-shirt and baseball cap wades through ankle-deep wetlands, holding an instrument in the air and peering towards the horizon. Her name is Patricia Medici, a Brazilian scientist whose work may more closely resemble extreme camping than the conventional image of “doing science.” For days, she and her team (which includes Sy and Nic) make trips around the vast Pantanal Wetlands of Brazil attempting to collar and track the elusive tapirs, whose behavior is largely a mystery. She has to beware pumas, venomous snakes, and the relentless bite of ticks, but the more troublesome battles are that with faulty equipment or inconsistent results. Although the subject of The Tapir Scientist and other books within this series is an animal, the text’s content is all process from the scientist’s point of view. Montgomery and Bishop record Patricia’s frustrations and triumphs as they happen and present their work as a narrative full of suspense, empathy and joy. Yes, the reader learns the traditional creature facts – anatomy, behavior, ecosystem – but all that report fodder is discovered only through the journey the reader makes with the scientist.

Similarly, Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wicks’ graphic novel Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas places its readers right in the boots (or bare feet) of the title’s three scientists. Through brilliantly distinct and sometimes overlapping narration, we grow to understand the individuals: Jane’s endless curiosity, Dian’s brusque fierceness, Biruté’s patient hunger. But all are united by their commitment to primate study, more so, to study primates in the wild. Each is recruited by famed anthropologist Louis Leakey, whose targeting of women feels ambiguously both progressive and sexist: he seems to respect these women for their observational intelligence, but Primates also references his womanizing with the young researchers he employs. Nevertheless, for these three women, chimps, gorillas and orangutans are the subject of all attention. The reader, too, is given a front seat to the observations; Wicks devotes pages of panels, with minimal text, just to the sequential movements and expressions of the primates: the chimps’ mysterious rain dance, gorillas’ unique noses “like big fingerprints,” an orangutan’s leisurely journey through the trees. Wicks’ style is not naturalistic; on the contrary, her brightly painted drawings are stylistically playful and simply rendered. Coupled with the type sets used for the texts, which mirror the style of each scientist’s documentation – handwritten script or typed Courier – the reader can imagine these illustrations appearing in these women’s scientific logs, a patient and enthusiastic recording of what they see in the field.

Similarly, Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wicks’ graphic novel Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas places its readers right in the boots (or bare feet) of the title’s three scientists. Through brilliantly distinct and sometimes overlapping narration, we grow to understand the individuals: Jane’s endless curiosity, Dian’s brusque fierceness, Biruté’s patient hunger. But all are united by their commitment to primate study, more so, to study primates in the wild. Each is recruited by famed anthropologist Louis Leakey, whose targeting of women feels ambiguously both progressive and sexist: he seems to respect these women for their observational intelligence, but Primates also references his womanizing with the young researchers he employs. Nevertheless, for these three women, chimps, gorillas and orangutans are the subject of all attention. The reader, too, is given a front seat to the observations; Wicks devotes pages of panels, with minimal text, just to the sequential movements and expressions of the primates: the chimps’ mysterious rain dance, gorillas’ unique noses “like big fingerprints,” an orangutan’s leisurely journey through the trees. Wicks’ style is not naturalistic; on the contrary, her brightly painted drawings are stylistically playful and simply rendered. Coupled with the type sets used for the texts, which mirror the style of each scientist’s documentation – handwritten script or typed Courier – the reader can imagine these illustrations appearing in these women’s scientific logs, a patient and enthusiastic recording of what they see in the field.

Lastly, Louis Nowra’s fictional novel Into That Forest portrays not a willing scientist per se, but a child lost in the woods. Incredibly, young Hannah and her friend Becky survive a storm in the Tasmanian wild, only to be rescued and adopted by two Tasmanian tigers. Initially they are terrified, but as the creatures prove themselves trustworthy guardians – bringing them caught fish, leading them to their den – the girls adapt to their bizarre new family structure. Over four years in the wild, they slowly lose the things that define them as human – their manners, clothes, and eventually, language – but they gain just as much in their careful observations of their new companions. Theiri senses sharpen, words are replaced by growls and eye expressions, and affection for their new foster parents grows:

Lastly, Louis Nowra’s fictional novel Into That Forest portrays not a willing scientist per se, but a child lost in the woods. Incredibly, young Hannah and her friend Becky survive a storm in the Tasmanian wild, only to be rescued and adopted by two Tasmanian tigers. Initially they are terrified, but as the creatures prove themselves trustworthy guardians – bringing them caught fish, leading them to their den – the girls adapt to their bizarre new family structure. Over four years in the wild, they slowly lose the things that define them as human – their manners, clothes, and eventually, language – but they gain just as much in their careful observations of their new companions. Theiri senses sharpen, words are replaced by growls and eye expressions, and affection for their new foster parents grows:

The tigers stopped being animals to me. They were Corinna and Dave… Corinna showed she liked us by licking us and curling up with us whenever we slept. Though I have to say, if she didn’t like something you did, she’d nip you to let you know.

Nowra’s story, as dense and rich as the Tasmanian forests, not only stands as an imaginative memorial to the thylacine, officially declared extinct in 1936, but as a testament to Piaget’s classic theory of development: that the child is a scientist, learning and constructing her world of knowledge through constant observation and application without any extrinsic motivation, like candy bribes or A+ grades. It is that childlike passion and curiosity that should identify grownup scientists more than the lab coats. Indeed, the women so masterfully presented in these varied stories all possess that drive for understanding the world that seems to exist outside of and above the status quo of our everyday work culture. And perhaps outside is the key: it is hard not to feel awed, inspired and motivated when you’re surrounded by the wonder of the wild.

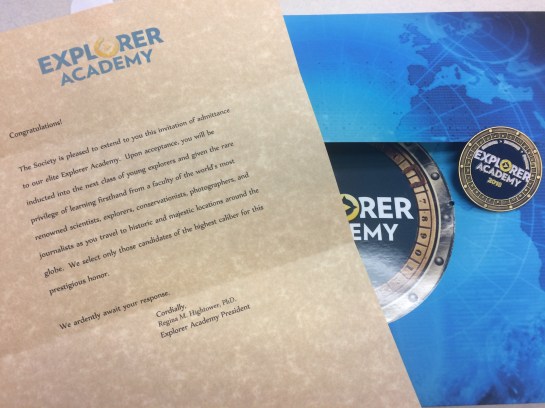

I was fortunate to spend my Wednesday afternoon with a lovely group of fellow book-lovers; professors, lit experts, book-sellers, and publishing industry insiders (oh, my!) at the lunch and launch of the new National Geographic Kids series Explorer Academy. The series will include seven fact-based fiction adventures for middle-grade readers that are inspired by the real scientists and explorers at the National Geographic Society. The first title in the series, The Nebula Secret, follows 12-year old Cruz Coronado and his fellow students as they travel the globe to become the next generation of explorers and possibly solve the mysterious death of Cruz’s mother. The blend of adventure, STEM topics, and world cultures is sure to appeal to a wide audience.

I was fortunate to spend my Wednesday afternoon with a lovely group of fellow book-lovers; professors, lit experts, book-sellers, and publishing industry insiders (oh, my!) at the lunch and launch of the new National Geographic Kids series Explorer Academy. The series will include seven fact-based fiction adventures for middle-grade readers that are inspired by the real scientists and explorers at the National Geographic Society. The first title in the series, The Nebula Secret, follows 12-year old Cruz Coronado and his fellow students as they travel the globe to become the next generation of explorers and possibly solve the mysterious death of Cruz’s mother. The blend of adventure, STEM topics, and world cultures is sure to appeal to a wide audience.

Trudi Trueit, the series author, is a weather forecaster turned writer that couldn’t help sharing her love for science with young readers. In our brief conversation, she proved to be a passionate advocate for readers, libraries, and scientists! She has tapped the knowledge of National Geographic Explorers (they are like the rock stars of the National Geographic Society) for the series to bring their real life discoveries, research, and innovations into the action-packed plots. Nizar Ibrahim, paleontologist and National Geographic Explorer, joined us to share his experiences with the NGS and a top-secret (sorry!) hint at some new discoveries.

Trudi Trueit, the series author, is a weather forecaster turned writer that couldn’t help sharing her love for science with young readers. In our brief conversation, she proved to be a passionate advocate for readers, libraries, and scientists! She has tapped the knowledge of National Geographic Explorers (they are like the rock stars of the National Geographic Society) for the series to bring their real life discoveries, research, and innovations into the action-packed plots. Nizar Ibrahim, paleontologist and National Geographic Explorer, joined us to share his experiences with the NGS and a top-secret (sorry!) hint at some new discoveries.