Bunny the Bra ve War Horse: Based on a True Story

ve War Horse: Based on a True Story

by Elizabeth McLeod, illustrated by Marie Lafrance

Kids Can Press, 2014

Bunny, a magnificent horse, and two brothers, Bud and Tom, ship out to Europe in 1914 among a group of police horses and officers sent to fight on the battlefields of WWI. Bunny is initially assigned to Bud, and when he is killed he becomes Tom’s horse. The two form a close bond, and survive the conflict together, performing acts of heroism and sacrifice along the way. At war’s end, however, the two are separated; Tom returns to Canada, and Bunny is sold to a Flemish farmer. McLeod tells Bunny’s story with a combination of poetic license and narrative restraint. Her straightforward prose tells Bunny’s story simply, without drama or sentiment. We experience the hardships of war–the hunger and danger and death–but the matter-of-fact tone with which they are expressed establishes Bunny’s and Tom’s resolute, impenetrable bravery. Lafrance’s folk-like illustrations reinforce this sense of plain strength. Spread across double pages, the images are a bleak amalgam of murky greens and greys, setting a desperate tone broken only by the brilliant poppies immortalized in Dr. John McCrae’s poem “In Flanders Fields.” McLeod includes an author’s note in which she explains just how much isn’t known about Bunny’s story (even “Bud,” the name given Tom’s brother, is an invention), and confirms the heartbreaking conclusion. The Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication assigns fiction subject headings to this title, and I’m inclined to agree. This is a fiction with roots in fact. But it is no less a powerful and touching evocation of the perpetual price of waging war.

Stubby the War Dog: The True Story of World War I’s Bravest Dog

Stubby the War Dog: The True Story of World War I’s Bravest Dog

by Ann Bausum

National Geographic, 2014

In stark contrast to Bunny, Stubby the War Dog is a presentation of a bodacious collection of scrupulously documented facts surrounding one formidable dog. Sergeant Stubby, as he was known, was a dog with a personality as outsized as his antics. He presented himself as a stray to the 102nd Infantry, training at Yale University in 1917, and so endeared himself to the soldiers that one Corporal Robert Conroy smuggled him onto their ship bound for the theater in Europe. From there Stubby’s infamy grew and grew. Bausum offers a series of almost unbelievable anecdotes–Stubby saluting the officer who discovers him as a stowaway, Stubby rescuing a French toddler from oncoming traffic, Stubby recovering from grievous injury sustained on the battlefield–which establish his irrepressible persona. She also surrounds Stubby’s own story with rich and extensive context, offering lots of information about the greater war and its impact on everyone it touched. The narrative follows Stubby back to the United States after the war, where he travels, parades, and generally contributes to the post-war effort, and even chronicles his story after death, and the eventual inclusion of his remains at the Smithsonian Institution. What is most striking about this masterful exposition, to me, is the journalistic integrity of Bausum’s language. She makes it crystal clear, at every juncture, what she knows and what she wonders, and how she knows the difference. At no time does the reader question the veracity of the facts being presented, yet the narrative’s careful precision never intrudes on the accessible flow of the story. It’s easy to imagine kids enthralled with Stubby’s bigger-than-life life. And it’s just as easy to imagine them fascinated by the curiosity that prompted the investigation and the research that followed. I consumed the story through the Recorded Books audiobook version, narrated by Andrea Gallo, and even the experience without a single image was riveting.

These two books differ from one another in interesting ways. One uses snippets of history as a foundation for a largely fictionalized story while the other offers a detailed account sourced from the (admittedly much more plentiful) historical record. Yet, almost counterintuitively, it is Stubby’s “true” story that brims with outlandish, colorful flourishes, while Bunny’s “imagined” account offers a much more reserved and stoic vision of the animals-at-war experience. And this juxtaposition, in a nutshell, is what I love so much about the work of librarianship for the young. It is not ours to determine which is the better, truer, more legitimate approach, We get to put these books on the self, together, and invite kids (metaphorically, or directly, too, if we want) to ponder them both.

The Caldecott terms and criteria constitute a particular, prescriptive lens through which to look at picture book illustration. The Caldecott Medal is arguably the most prestigious prize a picture book can win, and as such the specific elements and attributes it recognizes have a particular role to play as we examine and evaluate books in the canon. To be sure, the Caldecott terms and criteria are not the only measure we can apply. Indeed, in our day to day work with children, other things–iconic characterization, accessibility, suitability for a group read aloud–can be much more significant. Still, measuring picture books with the Caldecott measuring stick allows us to delve deeply into the quality of the illustration, and gives us meaningful information about the application and legacy of the Medal itself.

The Caldecott terms and criteria constitute a particular, prescriptive lens through which to look at picture book illustration. The Caldecott Medal is arguably the most prestigious prize a picture book can win, and as such the specific elements and attributes it recognizes have a particular role to play as we examine and evaluate books in the canon. To be sure, the Caldecott terms and criteria are not the only measure we can apply. Indeed, in our day to day work with children, other things–iconic characterization, accessibility, suitability for a group read aloud–can be much more significant. Still, measuring picture books with the Caldecott measuring stick allows us to delve deeply into the quality of the illustration, and gives us meaningful information about the application and legacy of the Medal itself.

The buzz leading up to the

The buzz leading up to the

For our winner we selected

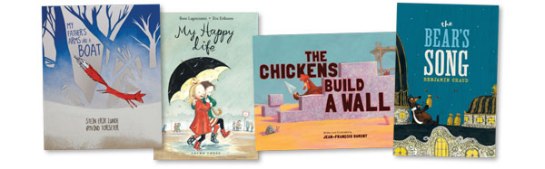

For our winner we selected Our honor book is My Father’s Arms Are a Boat by Stein Erik Lunde, illustrated by Øyvind Torseter (Enchanted Lion Books). A boy who recently lost his mother steps into the night with his father to process grief, look for comfort, and reconnect with the world that still holds possibility. Here we appreciated the untethered compositions, expressing the amorphous, rudderless nature of grief; the gradual relief that comes with the return of regular boundaries; and the expression of life’s fragility in the delicate three-dimensional paper-work dioramas.

Our honor book is My Father’s Arms Are a Boat by Stein Erik Lunde, illustrated by Øyvind Torseter (Enchanted Lion Books). A boy who recently lost his mother steps into the night with his father to process grief, look for comfort, and reconnect with the world that still holds possibility. Here we appreciated the untethered compositions, expressing the amorphous, rudderless nature of grief; the gradual relief that comes with the return of regular boundaries; and the expression of life’s fragility in the delicate three-dimensional paper-work dioramas.

On Thursday, January 16, our regular Butler Center book discussion group, B3, resumes with a bang. This time out we’re conducting a Mock Caldenott Award. Yes, you read that right. CaldeNott. We’ll be using the official

On Thursday, January 16, our regular Butler Center book discussion group, B3, resumes with a bang. This time out we’re conducting a Mock Caldenott Award. Yes, you read that right. CaldeNott. We’ll be using the official  So, we have a short list of a butler’s dozen (that’s 13) extraordinary picture books vying for the Caldenott crown. You can find the titles

So, we have a short list of a butler’s dozen (that’s 13) extraordinary picture books vying for the Caldenott crown. You can find the titles  Hope to see you there!

Hope to see you there!